tl;dr

- Reverse to find unique function not containing bad stack canary

- Libc leak using format string vulnerability in printf

- ROP chain to get shell

Challenge Points: 472

No. of solves: 26

Solved by: the.m3chanic, tourpran

Challenge Description

1 | Damn, I lost my canary at one of the train stations. Can you help me find it? |

Challenge Handout

1 | ld-2.31.so |

Step 1: Initial Analysis

Okay, we have quite an interesting handout for your average RE challenge. Makefile, libc, linker and Dockerfile?

Oh yeah, this is also a pwn challenge. :)

I like to get as many ideas/as much information as I can from everything about or surrounding the challenge as I can, as it usually gives me ideas on what to look for when I start the actual analysis process on the binary.

So, keeping that in mind, let us first inspect the handout files other than the binary itself.

1 | $ cat Dockerfile |

Okay, this tells us there is a flag.txt file in the server, which gives us multiple methods of approaching this challenge already. We can narrow down this funnel as we further progress with the challenge, finalising on one approach in the end.

Next up, let us look at the Makefile

1 | $ cat Makefile |

What we see aligns with the name of the challenge as well. We can see that the challenge binary was compiled with the -fno-stack-protector option, what does that do?

Well, before we discuss that I think a small refresher on the stack would be nice.

A Stack Refresher

(I will be using x86_64 as an example to explain)

The stack is used to store local variables (on a per-function basis) during program runtime.

It is also important to clarify the difference between 2 terms: “stack space” and “stack frame”.

Stack space is the space allocated by your OS for your current program, there is one stack space assigned per program, which is some amount of space in the RAM.

Stack frame is the “stack” structure itself which is used up per-function in your program - each function has its own stack frame.

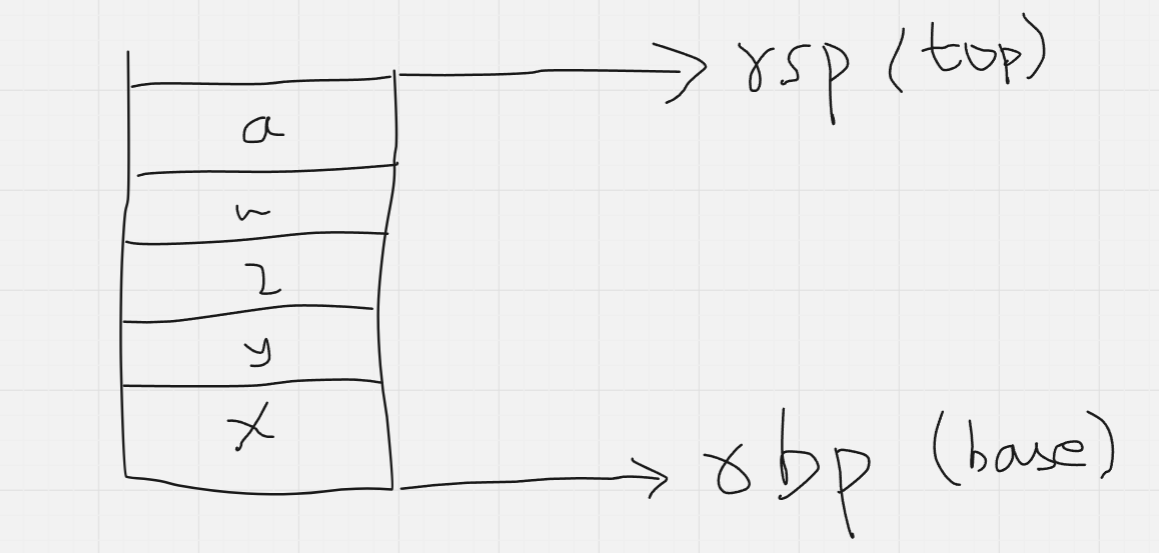

Stack frames are constructed and destructed for every function that executes, and there can only be ONE stack frame in the current context at any given time. That means, only one stack pointer (rsp in x86-64), which points to the top of the stack - whichever is in the current context, and one base pointer (rbp in x86-64), which points to the base of the stack in the current context.

So, if each function needs to have its own frame, we need a way to save each function’s base and top pointers, right?

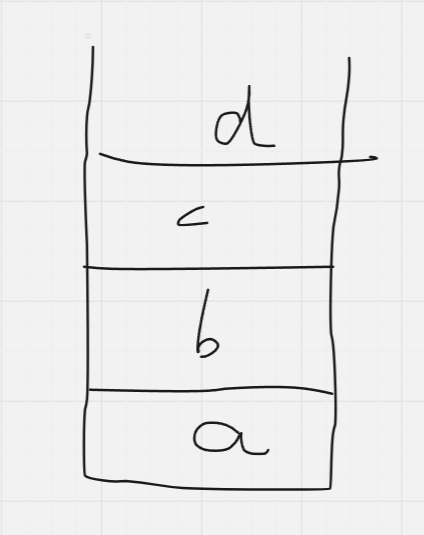

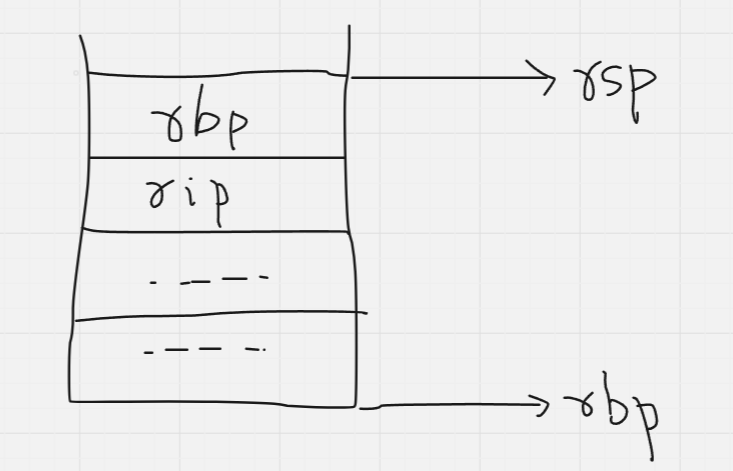

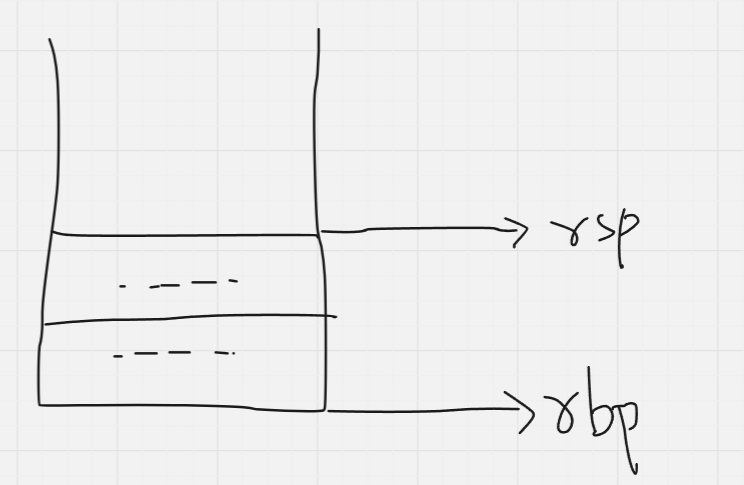

First, let us look at how a normal stack looks for a regular function (say main())

(In actuality, the stack grows downwards in memory, i.e, the stack pointer is the one moving down when the base pointer stays constant above it, but I am just drawing it this way for easier visualisation)

Okay, now we need to see how each function can maintain it’s own stack frame while the overall program still uses only 2 pointers - one for the current stack top and another for the current stack base.

Let us see how x86-64 handles this.

(I am assuming at least basic assembly knowledge at the time of writing this)

Okay, let us say we are in main, with source code as follows:

1 |

|

At the line of the call to find_sum(), the stack would have some values (these depend on the compiler you are using, but not of our concern anyways - what we are bothered with is the top and base pointers). Let us see the stack right before the call to find_sum():

(Note: The rsp and rbp only point to the top and bottom, they do not contain the values at the bottom/top of the stack - those can be gotten by dereferencing these pointers)

So, the next line is our function call, let us see what happens.

First off, every function call is translated into assembly as a call instruction, which transfers control flow to a different part of the code.

1 | # something like this |

We can see that there are also instructions after the call instruction, so once the different part of the code finishes executing, control flow would need to return to the next instruction (mov eax, 0, in our case).

Luckily for us, we have a register which tracks the address of the next instruction: rip. Let us use that.

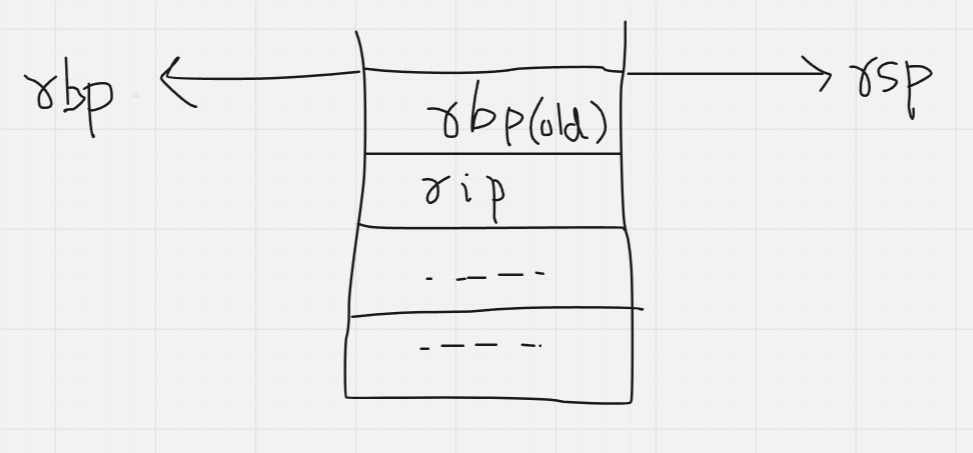

To store rip temporarily, we can push it onto the stack.

The call instruction in x86-64 is actuall abstracted into 2 separate instructions: push rip and jmp rip, so the control flow of our program is transferred there.

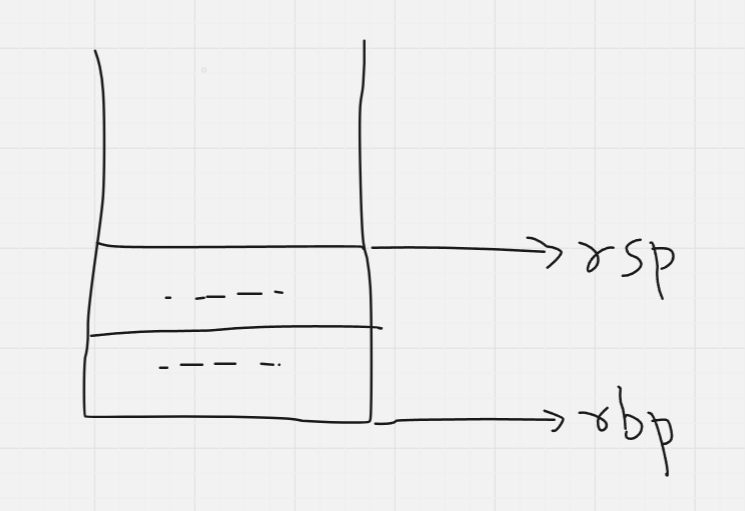

Currently, our stack looks like this:

Now, what Intel does here is interesting.

First, the old value of rbp is pushed onto the stack

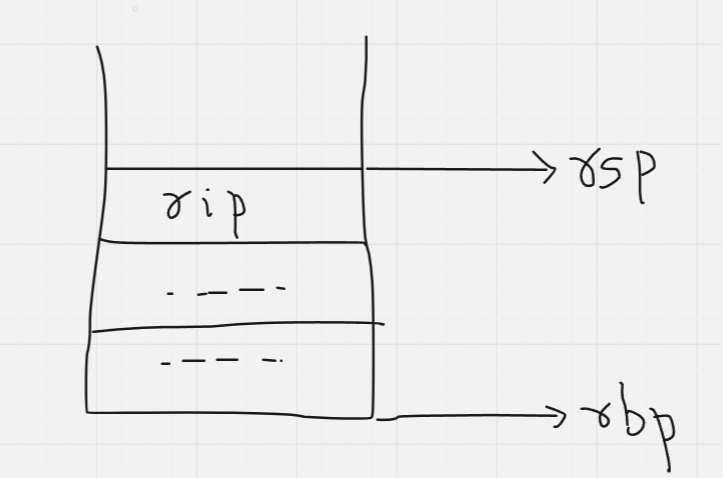

Now that the old rbp value is safe, the current top, is set as the new base (i.e, rsp and rbp now contain the same values, effectively pointing to the same address).

And now, the stack for the new function is set up! The function is free to use its frame however it pleases (as long as it does not use up all the stack space allocated by the OS!).

If we had to put what I just showed in pictures and translate it to assembly, it would look a little something like this:

1 | # save the old value of rbp on the stack |

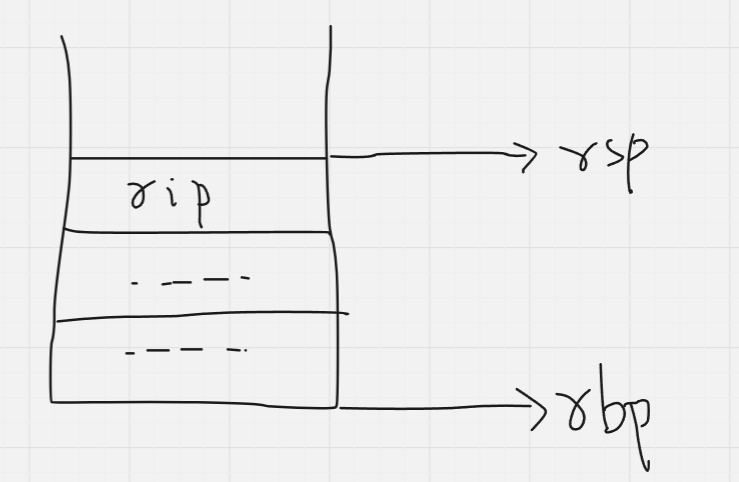

Now, logically, returning from a function would follow the opposite steps as setting up a stack frame for a function.

First, the stack top pointer is brought down to the current base (opposite of what happened for setting up)

Next, the top value on the stack (which was the old base pointer) is popped into rbp. This effectively moves the base pointer back to where it previously was.

Next, the top value on the stack (which was the old value of rip), is popped into rip (this is abstracted as the instruction: ret).

And that’s how it’s done!

This is how you can use just 2 pointers to effectively have however many stack frames you want (1 per function).

Now, back to the challenge :)

Analysis: continued

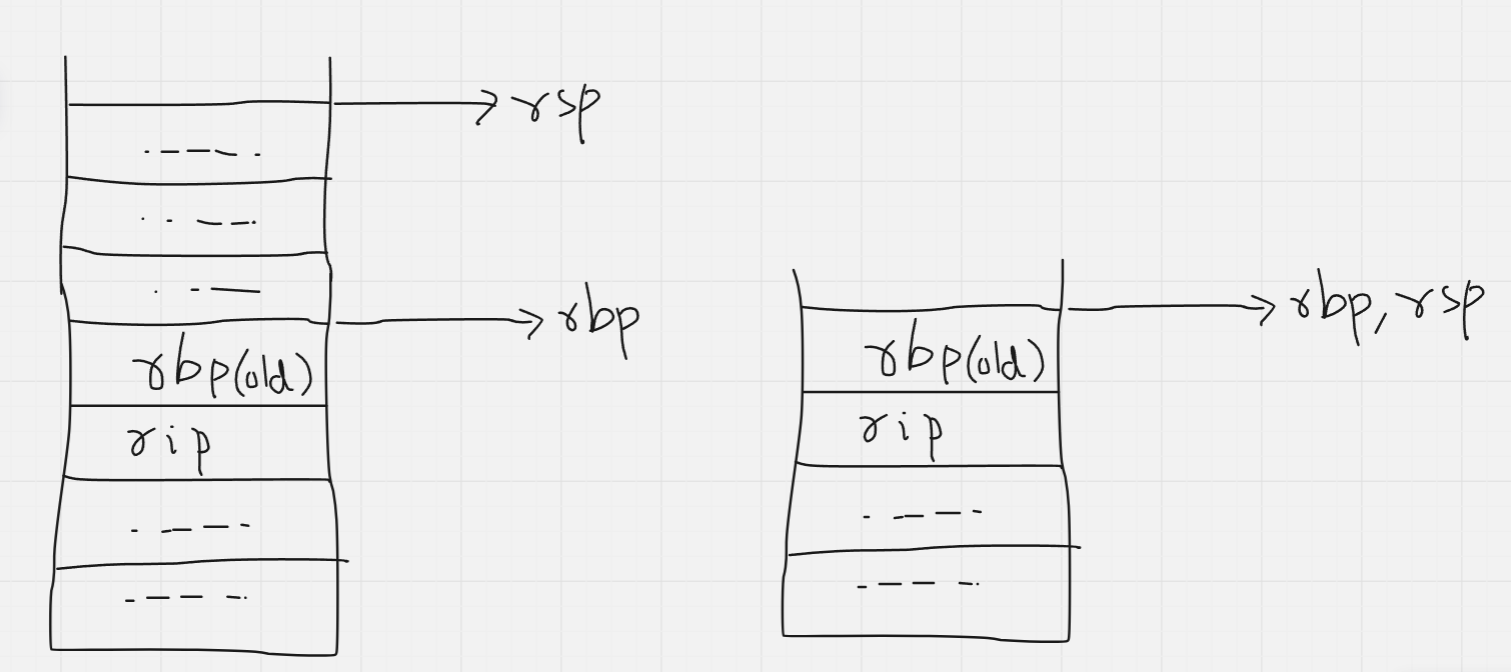

The -fno-stack-protector turns off the option to add a stack protection mechanism known as the “stack cookie” or the “stack canary”. Why does the stack need protection, though?

Well, we have seen that, during a function call, the stack stores 2 critical values: the old base pointer (rbp) and the return address from where code flow needs to continue after the function call (rip). What if I can overwrite these values?

What if there are some library functions (for example: gets), which use the stack as a buffer to store the value we give it, but do not perform any bound/size checks, and will accept any length of input and place it as it is on the stack? gets is one such example of a library function which does not care about the size of the input you give it, it will eat up as many characters as you give it.

This effectively means I can overwrite the rip with whatever value I want, meaning I control the flow of execution of the program going forward.

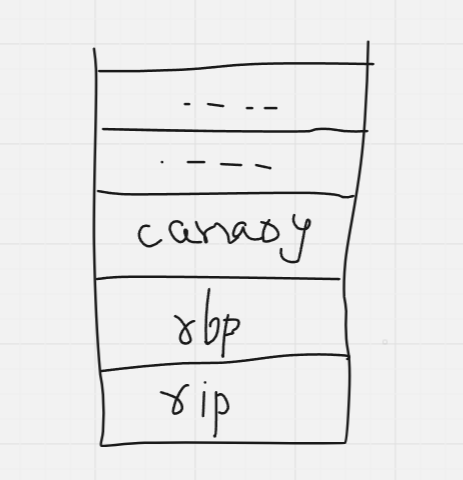

A stack canary is a kind of boundary wall that is used to prevent such attacks. It is a random value that is generated each time the program is run, and placed between the old rbp and any value(s) the function uses the stack for storing. So the new stack looks a little something like this:

The value of this canary is checked to see if it it was overwritten with something else. If it is not what it’s supposed to be, the program simply exits. It is difficult (but not impossible in some cases), to beat this.

Next up, -Wno-deprecated-declarations - this just tells the compiler to keep quiet and not warn about any deprecated function(s) we might be using in our program.

Step 2: Program Analysis

Before we try running the program, we need to make sure the binary is patched to refer to the linker and libc that we have been given in the handout. Luckily, there is a very handy tool for doing just this: pwninit.

Just install and run pwninit from the challenge directory and it will do the patching for you, and will generated a separate patched file, with the needed changes.

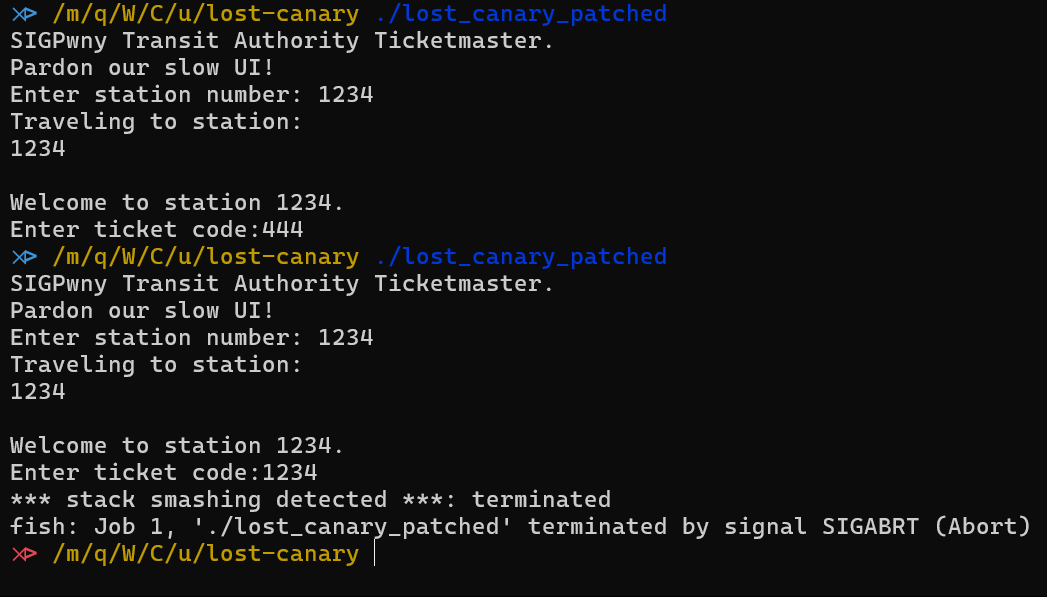

This is what we get from running the binary a couple of times, let us open it up in IDA.

Immediately, we can see a bunch of station_<number> functions, probably the function that gets called based on the station number we input, and it gets there using a jmp table. You can tell this because of the __asm { jmp rax } that IDA has placed in the pseudocode. You can recover any jump table in IDA if you notice this by following this blog.

In the select_station function itself, we can see there is a call to printf with the input that we give to the program. This is a format string vulnerability.

What is a format string vulnerability?

In assembly, there is something known as a “calling convention”. This refers to the places where any function looks at first when it is called, to know what arguments were passed to it.

In x86-64 the calling convention is as follows: rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, r8, r9. If a function has more arguments than this, the stack is used for the remaining ones.

This just means that, printf (and all other functions) will look at these registers in these order, followed by the stack to know what it has to print out to the console.

Now in our program, the printf call is vulnerable because it does not inherently control how many values it prints out. Compare the following 2 printf calls:

1 | printf("%s", arg); |

The first one is alright, because there is only 1 format specifier passed when printf() is called, and we cannot change that, but the second one is vulnerable - in the sense, we can print out however many values we want, in whatever format we want.

Before we get to exploiting this format string vulnerability, we also need to identify vulnerable functions, so how do we pick that?

Step 3: Reversing

A little analysis shows us that there exist 3 different kind of functions, functions that:

- Take ticket code through

gets() - Take ticket code through

fgets(), then usestrcpy()to copy it elsewhere - Take ticket code through

scanf()

All 3 have some or the other kind of BOF (buffer overflow) vulnerability, but there is one thing to keep in mind about each function here:

gets()stops taking input at the first newline (0xa)scanf()stops taking input at the first whitespace character in generalstrcpy()stops at the first null byte

(I kind of guessed that gets() would be the vulnerable function, it as well as could have been any other, in which case my script can be easily modified, but oh well)

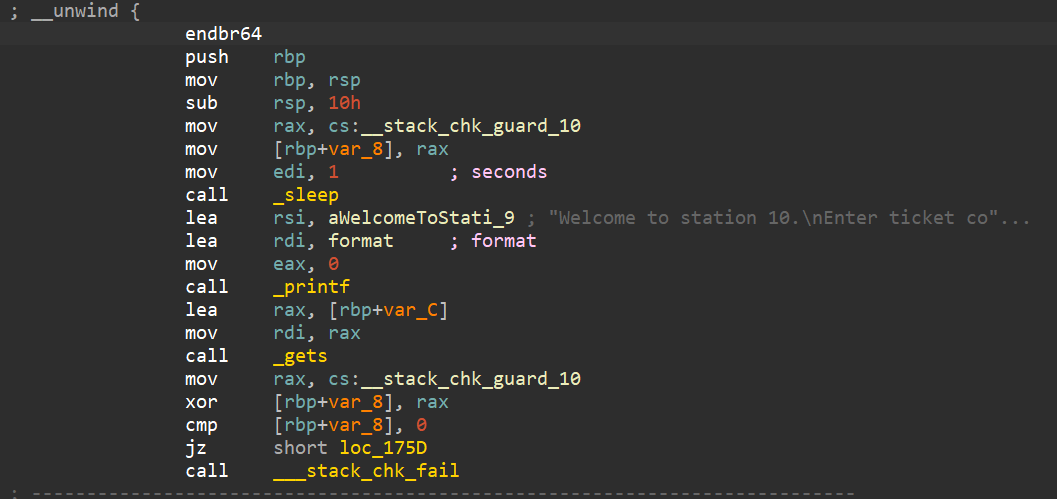

Let us pick a random gets() function and examine it.

Seems pretty straightforward, except one thing: a predefined stack canary is being loaded, not by the compiler. Meaning, we have all the stack canary values already, we would not need to spend timing finding/leaking it :)

Of course, the author would not want things to be this easy, so let us examine the canary as well

1 | __stack_chk_guard_10 = 0x456B0A4E4C74784F |

Ahh, there is a newline in there.

This is an issue because, if we do end up exploiting the buffer overflow vulnerability in gets(), we would need to keep the canary intact so as to not have the program detect an overwrite and exit.

To do this, we would need to pass the canary as part of the input, and doing that would prematurely end the gets() function since there is also a newline in the canary.

Examining a couple more stations shows us that this is the case for every gets() function so far, as well as scanf() and strcpy() functions

So, we need to find a single function where this is not the case. For this, we can utilise IDA scripting with the IDAPython API.

Here is the general idea:

- Generate a list of all functions calling

gets() - Generate a list of all stack canaries without a newline

- Compare to see if there are common functions between the two lists

So let us write a script to do just that.

1 | import idautils |

And the output of this script gives us the address of station_14927: the vulnerable one.

Step 4: Exploiting

Now that we have the vulnerable function, let us get down to exploiting it. From the Dockerfile we saw earlier, the idea is to get a shell and do cat flag.txt, so let’s see how we can do it.

Back to the format string vulnerability.

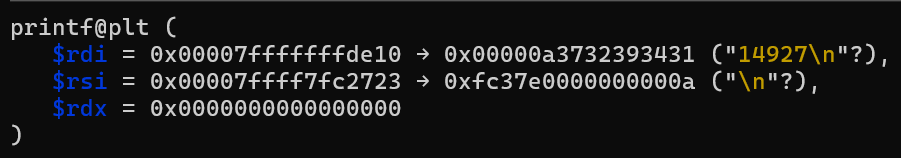

We know the printf() in select_station is vulnerable, and we know why. Let us view the register state before the printf() call in select_station

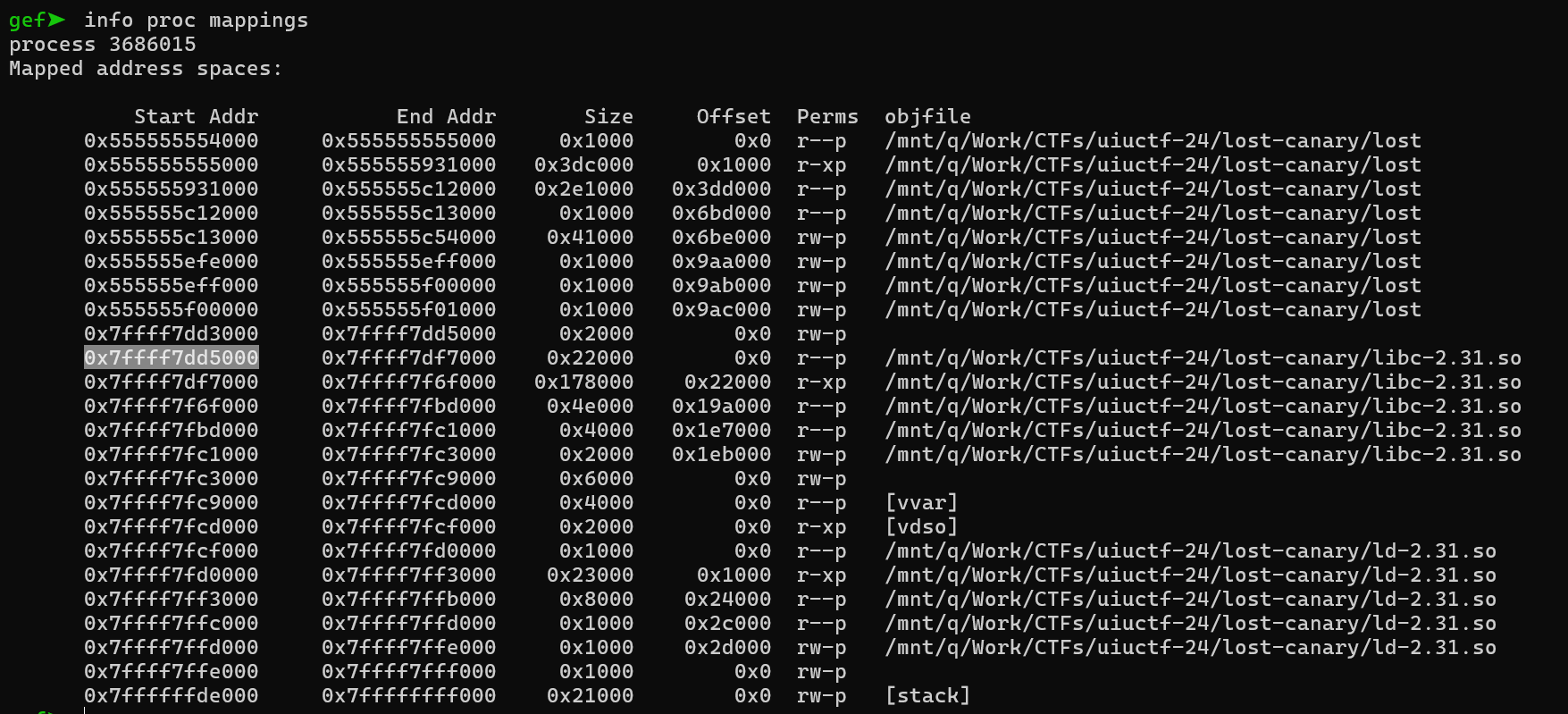

Running info proc mappings on GDB tells us what is mapped to where in virtual memory, so we can make use of that here

We can see that the address that rsi contains is actually a LIBC address!

We can assume ASLR is on for this program.

One interesting thing to note about ASLR is that while it does modify the actual addresses of variables and functions in your program, it usually does not touch the distance between these variables (this distance is also known as an “offset”).

For example, if we run a program for the first time, and a variable x is at address 0x1000, and a variable y is at 0x1050, and we run this program for a second time, we would see that the address of the variable x has now changed to 0x1450, but y remains a constant offset from it at 0x14a0.

This is because it would take way too long for ASLR to randomise the locations of every single variable in a given program. What is does instead is randomise the base address of various memory mappings, one of which is LIBC.

We can utilise this fact to find the base address of libc every time the program is run. This is known as a ret2libc attack

There are 4 main steps to ret2libc attacks:

- Find an address that points to something in the libc by using something like a format string vulnerability

- Use the address above to calculate the base address of libc

- Calculate addresses of any libc functions we like using the base address

- Use a different exploit (BOF in our case) to overwrite the return address with the libc function we would like to jump to

Let us leak an address as an example, by running the program with the input “14927-%p-“

The output I get is: 0x7ffff7fc2723

All I have to do, is subtract the base address of the libc I have (highlighted in the screenshot), from it, to get the constant offset difference, which comes out to be: 0x1ed723. I can use this information to get the base address of the libc every time the program is run now, through the format string vulnerability in main().

Return Oriented Programming comes in handy when buffer overflows allow us to overwrite a program’s call stack with what we want. Instead of us having to craft our own shellcode, all we have to do is take already existing pieces of code (known as “gadgets”) and put them together to craft our exploit - we will see how we can do that.

These gadgets are usually short bursts of instructions tailored to do specific things, each ending with a ret instruction. We can utilise this to control execution flow as per our will.

The beauty of ROP comes from it’s unique ability to harness code from any part of the binary (given it is executable).

First, we need to go gadget hunting to find what we need. Since we can write what we want to the stack, and we know rdi is the first place looked at by functions for their arguments, we would ideally want something that would allow us to pop the top value from the stack and into rdi, then perform a ret. Let us look for such an instruction in the libc with a tool known as ROPgadget.

1 | $ ROPgadget --binary ./libc.so.6 | grep "pop rdi ; ret" |

We can take the first one and ignore the rest. The output shows that at the offset 0x24b6a from the libc base, is the gadget we are looking for.

Next, we also need to find a ret instruction.

1 | $ ROPgadget --binary ./libc.so.6 | awk '{print $1 $2 $3}' | grep ret |

So ret is at 0x22679.

Now, we are ready to craft our payload that does the following:

- Send 4 “A”s and the canary to get to the return address on the stack

- Overwrite the return address on the stack with the

pop rdigadget - Set the value of

rdito “/bin/sh” - Overwrite the return address again with with the address of system

Let us see how this can be accomplished with a full fledged pwntools script

1 | from pwn import * |

So that is the entire challenge! A unique reversing + binary exploitation to top it all off.

If you guys have any questions about anything mentioned in the writeups, feel free to reach out to me or tourpran on X/Twitter at the.m3chanic, tourpran. Cheers.