tl;dr

- Custom hook to syscall 0x31337 using eBPF

- Check on the argument passed to syscall to verify correct/incorrect key

Challenge Points: 100

No. of solves: 61

Challenge Author: the.m3chanic

In this writeup I’ll be covering the challenge I authored for bi0s CTF, 2024.

I intended for this to be an easy warmup challenge for the players, and hopefully some people learned some new stuff from it as well :)

Challenge description:

according to all known laws of aviation, there is no way a bee should be able to fly

Initial Analysis

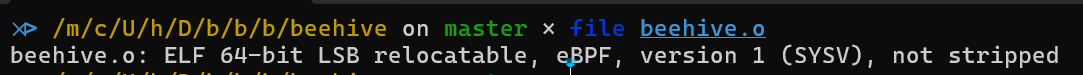

In the handout, there is a single file, beehive.o, let’s take a look at what kind of file it is

So it’s an ELF file, but of type eBPF. What is eBPF?

(I’m going to dive a little deep into eBPF and things surrounding it. If you’re only here for the solution to the challenge, you can skip to the solution)

Understanding eBPF

eBPF is a technology that can be used in the Linux kernel that is like running a very tightly bound (ability-wise) program directly in the kernel space. It is an event-driven language that can be used to hook kernel actions and perform specific tasks.

It runs natively in the kernel space with the help of a JIT compiler.

It’s basically a kernel level virtual machine that allows for programming of certain kernel level tasks, such as packet filtering, tracing, etc. Essentially a small computer inside the kernel that can run custom programs with restricted access.

Basically, think of it as a Kernel level javascript running inside a restrictive VM.

The obvious question that might come in your mind is - How is eBPF different from normal kernel drivers or kernel modules?

Well, the answer to that is simple:

eBPF programs don’t have nearly the amount of permissions as a regular kernel module, so you could say that they run in a much more constrained environment. They can’t make any drastic changes to the behaviour of the kernel, so this adds to their security and can help in reducing crashes. It’s perfectly in between a user program and a kernel program, in the sense that it runs in the kernel space, but with restrictions that differentiate it from an actual kernel module.

Now that we’ve got the basics out of the way, let’s get back to solving the challenge.

Our Approach

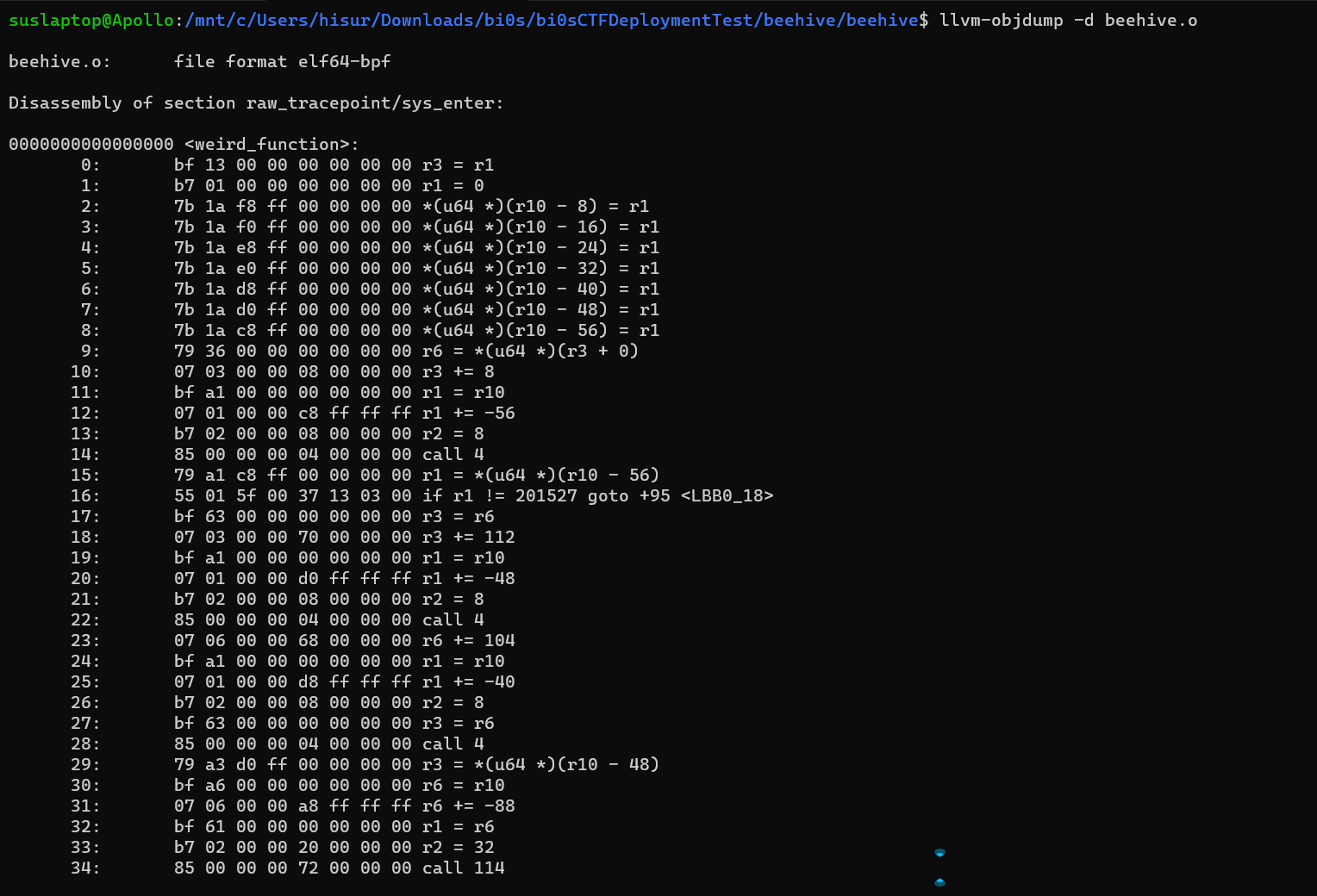

Some google searches tell us that eBPF can be disassembled using llvm, so let’s give that a try

Sure enough, we get the output, and in that we see a function called weird_function, now let’s take a look at what it does

One thing to keep in mind is: eBPF has its own instruction set architecture, so everything from registers to calling convention will be different

Quick overview of eBPF architecture:

1 | eBPF is a RISC register machine with 11 registers in total. Each 64-bits in size. |

Understanding the challenge

Now, the first few instructions from the dump kind of give us an idea of what’s going on here.

A bunch of stuff is loaded on the stack first, following which the last value loaded on top is later compared to 0x31337.

In eBPF, whenever a syscall is made, arguments passed to the syscall are pushed on the stack in reverse order, and the syscall number is pushed last (i.e, at the top). We can see that our program is doing something similar here.

We know that eBPF harbours the capability to hook onto syscalls on the kernel, so could it be possible that it is trying to hook onto syscall 0x31337?

Let’s confirm that hunch.

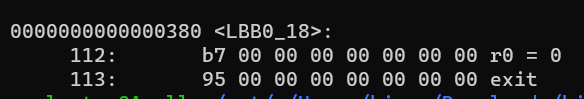

A failed comparison of the syscall number with 0x31337 leads us to label-18, which is

So I think we would need to make the syscall number 0x31337 to interact with this program. But what do we pass to it?

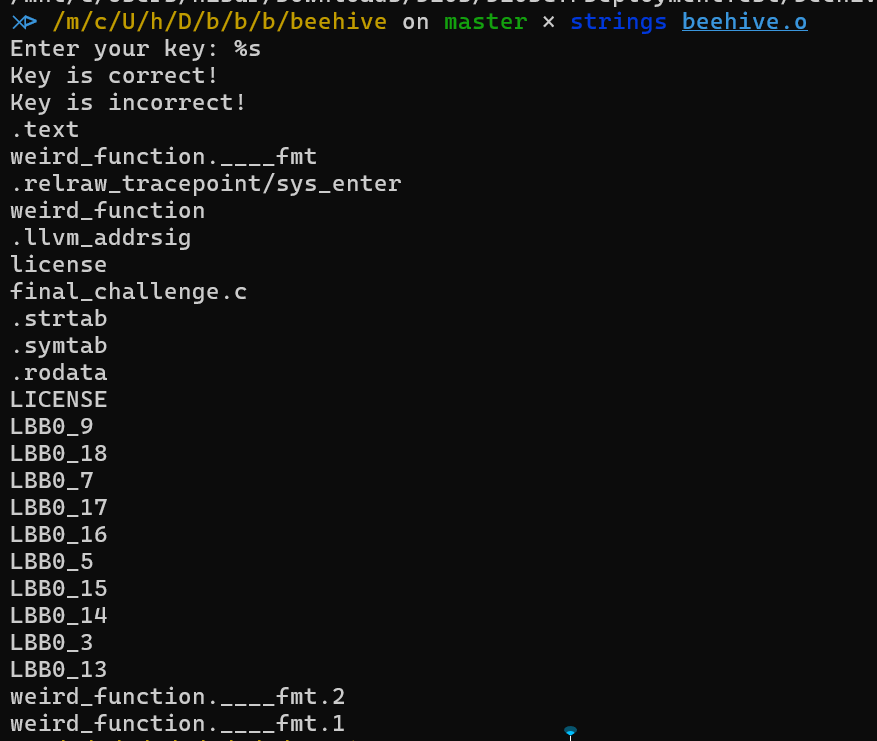

Seems like the program is asking for a key, and verifies that key for us.

Obviously the entire program can’t be efficiently analysed using just the object dump, so I will switch to IDA PRO for the remainder of this writeup.

By default, IDA is not capable of recognising this machine type, but there is a handy processor plugin that supports eBPF.

The output still doesn’t look too clean on IDA, so we can run the scripts on the processor repo to relocate maps and clean up eBPF helper calls for us.

(To run script files on IDA: File -> Script file -> filename.py)

The first few blocks of the disassembly seem to be telling us some pretty obvious things, it takes input, copies it to a kernel land string, then stores it.

How does it reference it though?

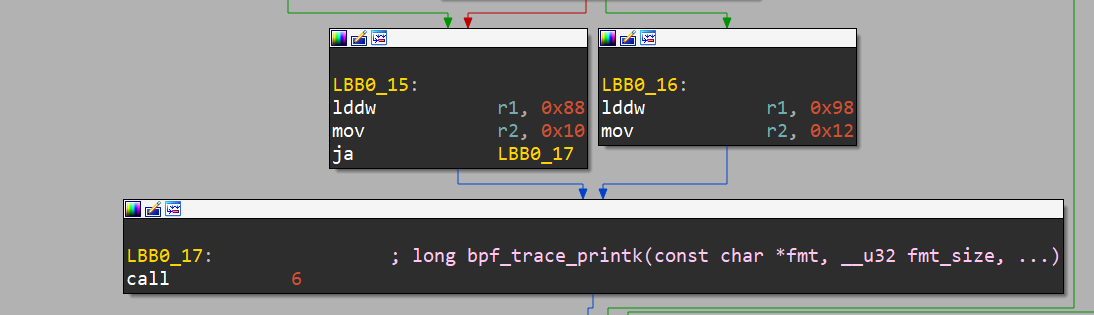

Let’s look at this logically - we know the binary has a print statement somewhere, and it prints 1 of 2 things

How is it referencing the correct and incorrect strings?

We can see some constants being loaded into r1 in each block, and that constant just happens to be the offset of the strings “Key is correct!” and “Key is incorrect!”, from the .rodata section. r2 just holds the length of the string to be printed.

I don’t want to get into too much detail about assembly level reversing here, so I will mention the required details, while trying to retain as much information as possible

1 | r1 --> loop counter for byte by byte encryption |

And, a python (almost line-by-line) representation of the encryption is as follows:

1 | def check(r5): |

Interacting with the program?

This is all very nice, but what’s a program that you cannot interact with?

Well, since this is an eBPF program, it’ll have to be loaded on the kernel and get past the verifier first, before we can actually make the syscall 0x31337 to trigger it.

How do we do that?

You can use this loader file to load the program and simultaneously read trace_pipe (where the outputs of bpf_trace_printk) are logged.

(Run this shell script first)

1 | sudo clang -O2 -target bpf -D__TARGET_ARCH_x86_64 -I . -c "$1"_challenge.c -o $1.o |

(Then, run this file to load the program)

1 |

|

Once loaded, you can write a python program to trigger the syscall with the arguments that you want to test it out (I used the ctypes module for this)

The Solution

Once you understand how the program manipulates your input, reversing it becomes quite trivial. The program simply takes each byte of your input, flips the bits (8 padded), then compares it with a preexisting array.

1 | compArray = [86, 174, 206, 236, 250, 44, 118, 246, 46, 22, 204, 78, 250, 174, 206, 204, 78, 118, 44, 182, 166, 2, 70, 150, 12, 206, 116, 150, 118] |

And that was my challenge! I hope you had fun solving it and (hopefully) also learned something new while doing it. :)